Full Circle: Why Funding Mental Health Research Isn’t Optional—It’s Life‑Saving

by Uma Chatterjee, One Mind Lived Experience Council Member

I almost didn’t make it to my 25th birthday.

For 25 years, I lived inside a brain that felt like a broken fire alarm—screaming danger and risk when there was none, demanding mental and physical rituals that swallowed every waking hour.

As an 8 year old, I spent every weekday evening hiding in the bathroom, reciting my set of 12 prayers in a cycle of 39 times. I’d work so hard to choke back my sobs because they would inconveniently interrupt this cycle and make me start all over again. And I knew that I had absolutely no choice but to complete these prayers perfectly… or else my parents would die on their way home from work and it would be my evil self’s fault.

At 16 years old, I totaled my first car (of 3) because I could not stop turning around to check my blind spot. How could I be certain that in the moment after checking my blind spot, a car would not somehow find its way there and I would then cause a car crash because I chose the “wrong” moment to check my blind spot? While that logic failed in the end… at least the totaled car only hurt me and nobody else.

At 20 years old, I could not go anywhere without my phone, iPod touch, two wall chargers, and two portable chargers. Why? Well, I obviously had to record every single conversation I had with any other human–friends, my therapist, coworkers, family, the drive-thru cashier–because I couldn’t possibly trust my own memory. I was probably an evil liar who made up my reality and harmed or manipulated every single person who ever had the misfortune of crossing paths with me–and recording everything was the only way that I could prove this. I always needed charged devices to accomplish this, of course. But even when I re-listened to these conversations and didn’t find the proof I was convinced existed, I couldn’t even trust them… because how could I know for certain that I wasn’t imagining the recording to be what I wanted to hear?

And as a 22 year old, I found myself to be at rock bottom: a college dropout, completely dysfunctional, fully housebound, sitting in the dark every night and unable to turn the lights on because I would cause myself and everyone I loved to become homeless. Every single minute of my life was consumed by horrific thoughts and images of me being a monster.

Untreated obsessive‑compulsive disorder (OCD), post‑traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), treatment‑resistant depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and bulimia nervosa turned every waking moment of my miserable life into existential crises. And the worst part? After two decades of living this way, not a single mental health professional could help me. Over 25 years, I cycled through twenty‑two clinicians, multiple hospitalizations, 18 different psychotherapy modalities, and more medications than I can list here–yet I only got worse. That was all the proof I needed to believe that I was indeed the monster my brain told me I was. By my mid‑twenties I’d dropped out of college with a 1.83 GPA, lost jobs, and considered ending my life daily because I truly believed I was beyond help.

Until one day, when research saved my life.

After decades of misdiagnosis and incorrect treatments, an OCD-specialized psychologist trained in exposure and response prevention (ERP)—a treatment studied and refined over decades of federally funded studies—finally named what was happening in my brain and taught me how to treat it. Within just weeks of beginning ERP, my entire life transformed. After going through my entire life thinking I was the most horrible person because of the uncontrollable intrusive thoughts I was having, I learned for the first time that, on the most fundamental level of self, not all of my thoughts are real. After losing faith in recovery, the only reason that I engaged with ERP was because I learned that about two-thirds of people with OCD improve with ERP, medication, or both. I’m only alive today because scientists fought for the grants and tirelessly performed the experiments and trials that made those statistics possible. For the very first time in my life, I felt like I may have a future on this earth.

Despite the respite that ERP provided, the severity of my mental illnesses required additional pharmacological interventions to provide meaningful relief. After exhausting every approved medication class without success, I entered clinician-supervised experimental protocols for ketamine infusions and psilocybin‑assisted therapy. Those psychedelic and hallucinogenic interventions—still in early stages of investigation—helped loosen the cognitive rigidity that fueled my OCD and depression, facilitated my brain’s ability to learn new ways of thinking and acting, and ignited my capacity to feel joy and hope for the first time. Psychedelics didn’t replace ERP; they biologically enabled my brain to engage with therapy. I needed both psychological and pharmacological treatments, born of rigorous research, to stay alive. Once again, research saved my life.

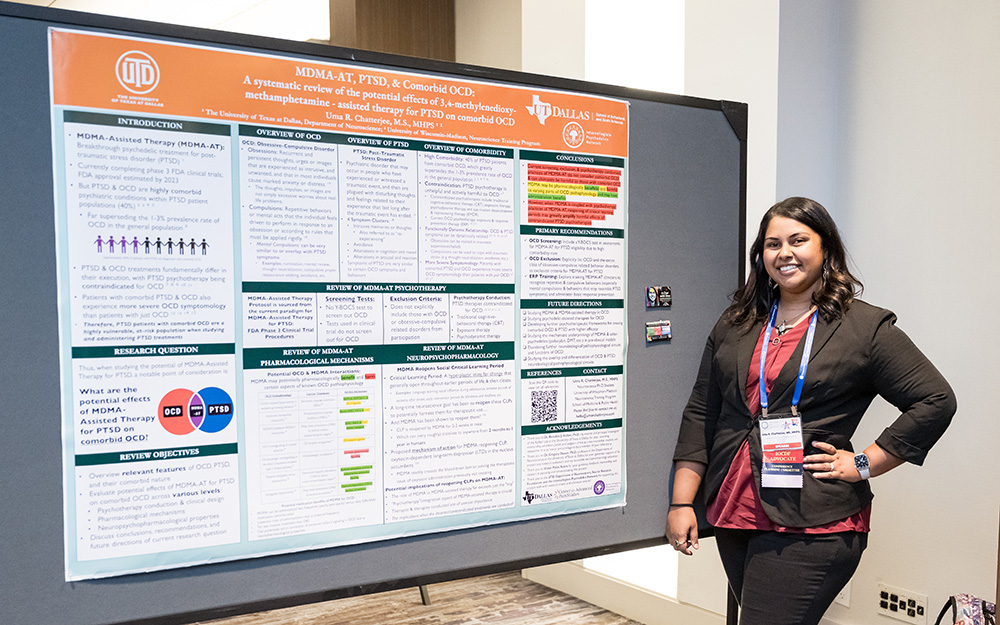

The transformation that ensued from research-driven, evidence-based treatments was so dramatic that I became an unrecognizable version of myself: I decided to go back to school to understand how mental illnesses worked in the brain and how we could treat them more effectively. I graduated college with all A’s, earned my M.S. in Neuroscience with a 4.0 GPA, and became an award-winning psychiatric neurobiologist and science communicator. In a truly full-circle way, I’m currently earning a Ph.D. in Neuroscience as an NIH TL1 Predoctoral Fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, studying the neurobiology of mental illnesses including OCD, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Bridging my lived experience and research, I’ve presented over 100 talks through keynote addresses, research symposia, and panel presentations at conferences and events worldwide to further both research and advocacy for underrepresented mental health disorders like OCD. My science communication and story has been shared with millions by major media outlets and top-ranked podcasts, my own podcast A Chat with Uma has reached thousands of listeners in 45 countries around the world, and I hold multiple leadership positions as the President of OCD Wisconsin, Advocate for the International OCD Foundation, member of several grant selection committees, and of course, member of One Mind’s Lived Experience Council. Today, I live a full, functional, productive, and purposeful life beyond my wildest dreams.

Unfortunately, the privileged position I hold of contributing to life-saving mental health research—also gives me a front‑row seat to a painful truth: mental‑health research is wildly underfunded relative to need. Mental illness affects roughly one in five adults in the United States (source), and serious mental illness drains the global economy of $1 trillion each year (source). Suicide is a heartbreaking leading cause of death (source). Yet, per-capita federal funding for brain‑disorder research trails far behind funding for other conditions (source) like cancer or cardiovascular disease when adjusted for disability burden. The result is a bottleneck: promising ideas stall, investigators trained for decades leave the field, and lifesaving treatments remain out of reach.

This year, that bottleneck feels tighter than ever. Ongoing budget negotiations have signaled possible cuts to the very grants and funding sources that make my own research and livelihood possible. As a result, my institution and countless others are cancelling admissions of graduate students, freezing hiring at all levels, and halting research projects. For patients waiting on the next generation of treatments, every delayed experiment causes further unnecessarily suffering. Life-saving and crucial clinical trials are being shut down, leaving patients counting on these trials with no options.

In these times of fear and uncertainty, I hold onto glimmers of hope and the power we hold with our stories and voices. Now more than ever before, we as advocates are raising large-scale awareness for the crisis in mental healthcare and stark gaps in equitable funding. As a result of advocacy, our current administration has recently signaled an openness to accelerating psychedelic research. As someone whose life was restored in part by ketamine and psilocybin, I deeply appreciate that openness to novel treatments. The therapeutic interventions that helped me may hold the potential to provide meaningful healing at large scale to countless treatment-resistant sufferers—if, and only if, we commit the dollars to run large, rigorous trials to assess safety and efficacy, and thoroughly dissect the mechanisms of actions that drive these compounds.

My story of survival, recovery, and transformation is not unique; it is simply visible. Millions of people—children, veterans, new parents, retirees—are one evidence‑based therapy away from reclaiming their lives. Conversely, millions more are still trapped because our current treatments fail them. Suicide remains a leading cause of death. Investing in research is not charity; it is infrastructure.

And let’s be clear: stigma is expensive. When policymakers treat mental‑health funding as discretionary, they ignore the hospitalizations, disability payments, and human potential squandered in its absence. Every grant I write is, in effect, a petition to be taken seriously—both as a scientist and as a person who still needs this research to continue surviving.

What you can do today:

- Contact your representatives. Tell them you value robust NIH and NSF budgets and targeted mental‑health initiatives. Share a personal story; stories change votes.

- Support organizations that fund high‑risk, high‑reward brain research. Private and non-profit philanthropy often seeds the very discoveries federal agencies later scale, as exemplified by One Mind’s Rising Star Awards.

- Combat stigma in your circles. Speak about mental illness the way you would diabetes or cancer; the cultural shift fuels the policy advances.

- Listen to lived‑experience voices. Patients are experts in outcomes that matter. Include them on advisory boards, grant panels, and conference stages.

I write this in between finishing a therapy appointment and beginning an experiment looking at the role of a particular gene in the neurobiology of OCD—because yes, I still attend ERP sessions 3 times per week and practice my skills daily. That continuity of care and research is what keeps me thriving, functional, and holding a pipette instead of holding on for dear life. If the current funding climate worsens, my mental health research will stop. But so will the hope of someone, somewhere, whose brain is screaming like mine once did.

I’m not advocating for special treatment; I’m advocating for parity. Parity with other illnesses, parity with the scale of the problem, and parity with the promise of what we can accomplish when mental health research is prioritized and supported. I am living, breathing proof that research turns the impossible into possible. Let’s make sure the next generation of individuals with mental illnesses—and scientists who tirelessly work to study them—has the same chance.